Let’s face it… A slate roof is nothing much more than a load of gaps with stones around them. How come it’s supposed to be waterproof?

The slates need to be arranged carefully so that any water that drains from a slate will hit the flat surface of one below and avoid any gap between them. To help that happen, you’ll often find that a natural slate roof (like ours at St Andrew’s) is made with large slates at the bottom and then slightly smaller ones as they climb towards the ridge. Have a look when you next come to church!

The slates need to be arranged carefully so that any water that drains from a slate will hit the flat surface of one below and avoid any gap between them. To help that happen, you’ll often find that a natural slate roof (like ours at St Andrew’s) is made with large slates at the bottom and then slightly smaller ones as they climb towards the ridge. Have a look when you next come to church!

Top nail – or middle nail?

It would seem to make sense to nail (or peg) a slate from the top, rather than making holes in the middle of your slate. Indeed, when cladding a wall (vertical slating), that is often done. However, in a wind these slates will easily be lifted up and blown off. A centre-nailed slate cannot “hinge” and is held down more securely. Many roofs are nailed down (nowadays, using stout aluminium “clout” nails) but older roofs may be fixed with wooden pegs that simply hitch behind the roofing battens.

Front or back?

If you look at a slate carefully, you’ll soon see that it has a definite front (outer surface) and back. The outer surface has a bevelled edge and the nail holes are countersunk so that the nail heads don’t make the overlying slate sit proud. Of the eight ways round you could place a slate, only one is correct!

The headlap

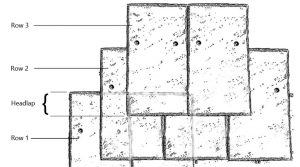

This overlap is the essential feature that keeps a stone roof weathertight. Water that runs from the bottom of a slate is bound to find the gap between the slates immediately below, so it is crucial that there is another slate below that to catch the drips. This overlap is called the headlap and should be at least 75mm.

It is the growth of vegetation in this crucial small overlap that is causing our current roof to leak.

Chris Wright

Article from ‘The Bridge’ September 2017